Looking Down at the Stars – guest post by Christina Riley

Posted on November 3, 2025

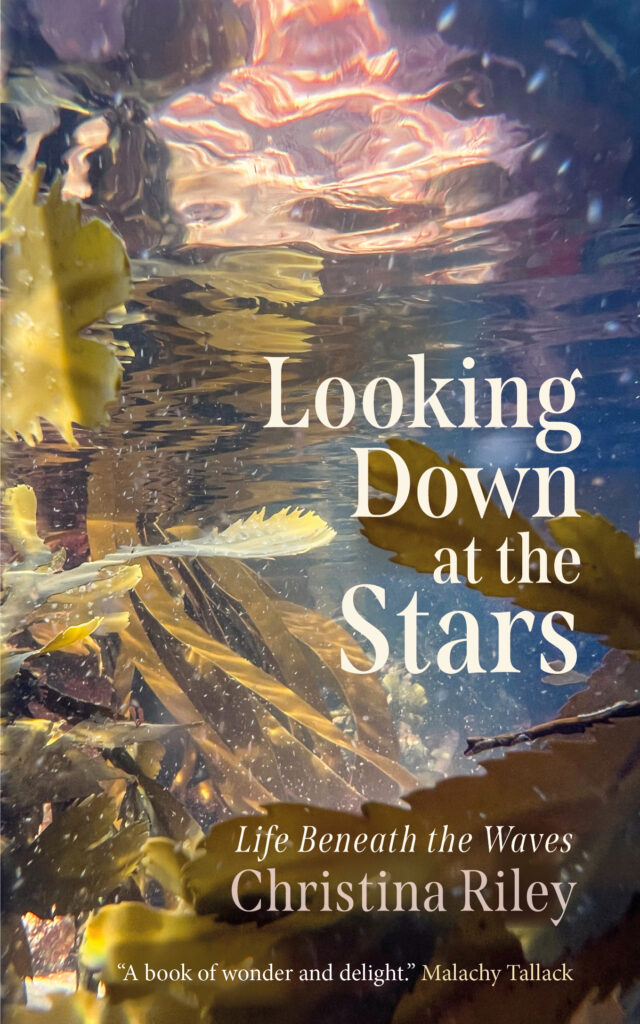

When I applied to be an underwater artist-in-residence at the Argyll Hope Spot my plan wasn’t to write, but to look. I’d been taking underwater photographs with various waterproof 35mm cameras, either disposable or effectively so, given how quickly they broke. The call for artists to spend time within the marine habitats of Scotland’s west coast felt like something I had personally commissioned and it was the most passionately and effortlessly truthfully I’ve ever filled out an application. As I wrote in Looking Down at the Stars, if I wasn’t right for this, I wouldn’t know what I would be right for.

Photography has always been the core of my practice and it’s what I wanted to develop further during the residency. Writing came later, and for a while felt like a separate entity. It wasn’t until the residency that the connection between the two became apparent. I went to the Argyll Hope Spot as a photographer, but as it turned out, the results of my underwater photography were underwhelming. Disappointing, but not necessarily surprising given how little experience I had and how much this landscape, light and physicality differs from what I’m used to. For example, taking a camera underwater is like putting invisible sunglasses over the lens. It looks the same to the human eye, but for the camera lens, only a little light is still getting through. This means that the best, arguably the only, time to take the camera underwater is when bolstered by a beaming sun. Our first weekend offered this, but the second was softer, wetter, heavier. I kept shooting, ever hopeful.

The results — tangled seaweed tresses and shadowy black brittle stars, contorted corpses sprawled on the ocean floor as though electrocuted — might have their merits for some situations, to some people, on some days, but they were not an accurate representation of what I saw and felt. They didn’t make the world feel like it was tumbling open and letting all the light and colour it’s made of spill out.

Thankfully, I was taking notes throughout the residency, mostly as a tool for remembering. Throughout school and college I kept a retrospective diary; rather than filling it with what I had coming up, I spent each morning filling it out with what happened the previous day. The detail is absurd at times. I would note that I bought honey, or milk, what I ate for lunch and what I read during it. In earlier diaries I’d note who was in attendance at the club, and what I watched when returning home at 3.30am. It’s the kind of note taking I still do; I worry that if I don’t, I won’t remember.

These essays, or vignettes, come from these fragments of notes taken down on paper, on a phone, or wherever I’ve managed to grab hold of something in time. Each one focuses on one species. In an environment so vibrant and alive the water pulsates with tendrils and tentacles and it’s difficult (but I won’t say impossible) to illustrate what it feels like, looks like, as a whole. I saw it instead as something like the pages of a natural history book filled with isolated drawings, not only of the starfish but also colourful anatomical etchings of its heart, microscopic representations of the underside of a sea star’s arm, which in fact isn’t their arm at all, but a branch of their head.

The resulting book takes the reader from the shore to the seabed, a habitat vast and vital and generally unseen, and attempts to show the reader some of the miraculous life in between. I’m interested in how attention to these species and the way they live can help me to understand how humans, one of almost nine million species on earth, fit amongst the rest. I’m also, just as much, interested in understanding nothing at all. It’s why I love to read and why I take photographs, to learn or feel or see something new. I don’t think I photograph many things that I understand, it tends instead to be things that make my eyes wide with curiosity; the camera comes out so that I can look at it again later, or as proof that it exists, that it happened. It turns a happening into a memory, or a story.

Each piece in Looking Down at the Stars is in a way a substitute for the photographs I, in the end, did not take. Which is not to say that the substitute is lesser for it. Writing is a different way of looking at things; the written word and the photograph are two ways of saying “Here, I want to share this with you”. Isn’t it beautiful? Has it made you change the way you think? I think it can. Beauty, I mean. I think the presence of and attention to beauty can change the way we think, how we see, maybe what we value. The question of value was on my mind a lot when writing but I think, really, I was mostly thinking about beauty and how fortunate I am to be alive in a place so full of it. More than I’ll be able to witness in a lifetime. More than any of us will ever know. I hope I’ve managed to share just a fragment of it with this.

Looking Down at the Stars: Life Beneath the Waves is publishing on the 6th November 2025.

Looking Down at the Stars: Life Beneath the Waves is publishing on the 6th November 2025.

Christina Riley’s lyrical prose is the perfect guide to this unfamiliar underwater world, brimming with surprises, sunlight and sea stars. The book also features some of her own beautiful black and white illustrations.

Join Christina at the Looking Down at the Stars book launch, taking place at The Portobello Bookshop on Thursday 13th November.

Christina also has an event at Mount Florida Books in Glasgow, on Saturday 22nd November, tickets available now!